Design from/for Systems of Boundary Objects

Design from/for Systems of Boundary Objects:

Retrofitting Obsolescence & Encounters at Interfaces

This post traces the development of my term project, through in-class planning, an encounter with seemingly obsolete research media, a discussion of digital rubbish, applications of the concept in ideas and pedagogy, some theoretical groundings, and a brief view forward.As I've stated in a previous post, my project this semester centers on the idea of retrofitting obsolescence. In simplest terms, this is an attempt to understand not just how technology and technology use changes over time, but specifically how users encounter old and seemingly useless technology in new an innovative ways. If retrofitting is a way of troubleshooting and engineering to give old objects (and possibly ideas) new meaning, and obsolescence is the state of being outdated or no longer useful, then retrofitting obsolescence is a special kind of creativity. It is a kind of giving that breathes new life--something worn and familiar flourishes again. But beyond the flashy appeal of brand new consumer goods, retrofitted obsolescence is attractive because it merges novelty with the familiar. Perhaps retrofitted obsolescence is just imagined nostalgia solidified in material form.

My idea map from our dry-erase day in class was expansive. Apparently I'm still learning the virtues of negative space as my mind-mapping sprawled an entire board space plus two little handheld units. The original ideas appear below in several parts of an installation.

Figure 1. Mindmapping my term project through class terms and too much space

What makes this computers and writing scholarship?

The question I asked (and unknowingly wanted to be asked) about my research was "what makes this work research in computers and writing?" This invariably leads to the question: "what is computers and writing scholarship?" Is it scholarship about using computers to write? Is it a matter of digital or multimodal composition? Do computers need to be networked? Is this just about composition or does digital access of writing count too?Engaging the literature (on its own terms)

One unanticipated point of intersection between this project and another project I'm pursing that centers on citation and revision practices came in the form of an article I requested via interlibrary load that arrived on microfiche.I came across Gail Hawisher's citation for "The Effects of Word Processing on the Revision Strategies of College Students" in Google Scholar and since our library did not have access to it, I requested it via ILL. It happens that this is one of the first academic papers Hawisher ever delivered at an academic conference and appears to be the basis for her earliest publication (see Hawisher's CV).

Hawisher reports an empirical study of 20 advanced college freshman in which their revision strategies were observed. 10 students used pen/paper/typewriter and the other 10 used word processors. Her findings across 80 essays was that "writing on a computer did not lead to increased revision." Of course, this study was conducted in 1986 so I'm sure a follow up study has been conducted (or should), but I focus on this article not so much for what it found, but rather, how I found it.

Microfiche must be among the most obsolete forms of data storage, and yet so much information for the latter part of the twentieth century is stored on film. It is much more compact than paper, but without a reader, it is functionally useless. Here's where retrofitting obsolescence comes in.

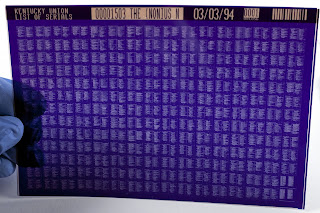

Hawisher's article arrived at ILL in a manilla envelope. It looked about like this:

Figure 2. A sample microfiche slide. Each small cell is a standard page.

Fortunately, the HSSE Library at Purdue University has several different readers and reference librarians are happy to help. Most of the old machines are essentially big light projectors designed for viewing. A more contemporary microfiche reader is designed to interface digitally with a PC that is connected to a laser jet printer.

Figure 3. A digitally interfacing microfiche reader in HSSE library at Purdue University

Figure 4. Retrofitted technology allows obsolete media to be read. Hawisher's 1986 title page.

Navigating from page to page involves physically moving the slide under the small digital camera. The process is not automatic; it requires physical dexterity in making small adjustments across the x and y axis. Focus and scaling for each page is also a manually adjusted fit. But once the page comes into clear and full view, printing a paper copy of the display is as easy a clicking an icon.

My point in sharing this extended research narrative isn't so much to engage a kind of show and tell as it is to highlight another feature of my research in retrofitting obsolescence. It isn't just hardware that becomes obsolete. Media that requires specific hardware for access can become obsolete when hardware goes by the wayside. Fortunately, some media (such as microfiche) are designed so that they can be read using a basic class of technology instead of some particular specific type. The shift from big outdated microfiche projectors to compact digital viewer was an obvious transition. And wile it might seem that the reader is what changed, what really matters is that the film can now interface with a digital platform. Had I not wanted to print each page, I could have used a thumb-drive to capture the images in digital form just as easily.

Were it not for the archivist who decided to store this conference presentation on microfiche, I'm sure the words would have been lost. Similarly, had it not been for librarians who allotted space and money for good film readers, the content would be unreadable. Retrofitting obsolescence is what makes usefulness out of what might otherwise just be trash.

Obsolescence and Digital Rubbish

In working to stay with the open access theme of this course, I'm doing my best to work with OA sources. To be sure, this means leaving many the resources I've encountered in other classes off the table. I will, almost certainly, include these resources in my final project. They have, after-all shaped so much of my learning and thinking so far. But, the quest in looking to OA sources has turned up some solid work, one of which is entirely predicated on the concept of digital rubbish.

In Digital Rubbish: A natural history of electronics (2011), Jennifer Gadbrys leads readers through a thoughtful consideration of the material consequences of digital ubiquity. Drawing on thinkers such as Harraway, Benjamin, and Serres, Gadbrys seeks to develop a theory of waste. At the center of her argument about the material consequences of the digital revolution is the point that digitization, like other phenomena in capitalism, works by relocating material consequences. An early example Gadbry's provides is the (now obsolete) case of piles of ticker tape filling up the floor of the New York Stock Exchange: each character printed on the thin strip of paper represents some material transaction that took place at some other point on the globe.

Figure 5. A pile of ticker tape recording material transactions via stock trade

Similarly, the seemingly virtual an immaterial digital cloud is supported by a massive network of physically intensive servers. Server "farms" are being constructed constantly in order to keep up with demands for information access and digital storage capacity.

Figure 6. One of Google's newest server farms

Gadbrys reports that, "Worldwide, discarded electronics account for an

average 35 million tons of trash per year. Such a mass of discards has

been compared to an equivalent disposal of 1,000 elephants every hour"

(emphasis added). To Illustrate and emphasize this startling figure, she goes

on to pain a picture of " A colossal parade of elephants—silicon

elephants—marching to the dump," such that "suddenly, the immaterial

abundance of digital technology appears deeply material." While the

motivator for her thesis is the sheer quantity and consequence of digitally

incurred waste, Gadbrys also probes interface feature of technology use

In a chapter on "ephemeral screens" Gadbrys argues that the digital jump to screen monitors was perhaps the most significant way of disjointing the experience of the digital revolution from its material consequences. Gadbrys states that "by articulating this relationship between signal and thing, my point is not to draw a direct and unproblematic line between these but, instead, to discuss how the signal and the thing are bound into shared material processes.” This inescapable materiality is similarly at the center of retrofitting obsolescence.

While there is much more for me to work with in Digital Rubbish, perhaps the most significant element it has imparted on my project is a more careful consideration of terms. Afterall, while Gadbrys' work with digital rubbish is very close to my interest in obsolescence, trash is not the same thing as reinvention. To sort out some of this related terminology, I've been developing tables:

Term (nouns)

|

Description or context of use

|

Refuse

|

Trash, Rejected

|

Waste

|

Unused and unsalvageable byproduct

|

Residue

|

Material left behind from a process. Evidence of previous happenings. Memory materialized.

|

Antique

|

Old object, usually with a history. Sometimes considered valuable (monetary or sentimental)

|

Garbage

|

Unknown etymological origin. Synonymous with trash. Sometimes collected and deposited. Often transferred.

|

Remainders

|

Similar to residue, but perhaps more substantive

|

Rubbish

|

Similar to garbage, but often appearing unwantedly. In need of being relocated.

|

Table 1. Nouns related to obsolescence

Term (adjective)

|

Description or context of use

|

Retro

|

Before, previous. Connotations can be positive or negative

|

Outdated

|

Past or beyond ideal date of use.

|

Obsolete

|

No longer produced or used. When broken, it can be difficult to find replacement parts.

|

Expired

|

Beyond prime date. Potentially harmful or less potent than expected.

|

Antonyms

|

Description or context of use

|

Preservation

|

To keep or maintain, either for use or for display or record.

|

Recycling

|

Usually materially, to reuse constituent parts (rather than send to a landfill)

|

Constructing these tables has been helpful for a few reasons. For one, encountering Gadbrys' book gave me the feeling that I had [almost] discovered someone else who already wrote the same idea I'm working through. I can now say "almost" because plotting out these terms allows me to see how my work is different, in essence, how it's not about trash, but rather finding one more use for technology before it becomes trash. Further, I'm realizing that tables like this are not just useful for me to create and reference as a writer, but they make also make information far more palpable for readers--easier to skim, to see order, and far less impending that a single wall of text.

So as I continue to situate my work within the literature on obsolescence and digital rubbish, I also want to gesture toward two further applications I'm working on before concluding with anchoring this all some some broader theory.

Retrofitting Obsolete Ideas?

The term "obsolescence" almost always applies to material objects. As I work out cases of physical retrofit, I'd also like to consider the ways in which ideas might be obsolete be retrofitted. In the most accessible example, I'm thinking about the way scholarship repurposes or "retrofits" previous scholarship through various citation practices to take on new meaning in the author's original work.It also seems like ideas or the ethos of cultural moments ebb and flow. Trends in fashion and technology rise and pass, but so does the popularity of ideas. Take for example, the momentum of social revolutions, moments when many people mobilize behind an idea and take visible action upon it. A few examples that some to mind are the various student movements that happened globally in 1968 and the 2012 Occupy Wall Street movement. Both were intense social actions stirred largely by resistance and direct activism. But these ideals seems to have subsided. Have they become obsolete? If so, can they be retrofitted? If things can be retrofitted to serve a new purpose, why can't ideas be repurposed too?

Figure 7. Occupy Wall Street demonstrators in 2012

Retrofitting Obsolescence as Pedagogy

When I first encountered the USB Typewrite that inspired the retrofitting technology concept, I was deeply drawn to the open access plans that the inventor provided online. He is no longer making or selling the USB Typewriter, but the existence of these plans makes the narrative that much more interesting. Retrofitting obsolescence isn't something we can just purchase, it involves actual work and planning.This summer, I'll be teaching a section of Technical Writing. Many of the students in Technical Writing are majoring in engineering or otherwise far more familiar with design plans for electrical arduino switches than me. To be entirely honest, the plans are incomprehensible to me. But I wonder if my students might be willing to work on this.

Initially, I was highly optimistic and drawn to the possibility of having the class actually construct a USB Typewriter. It's not totally out the picture, but the more I think about it the more I consider things like cost, safety (constructing electrical switches), and the overall amount of class time this could consume. So I've reconsidered.

When I think about the theoretical goals of the project, I'm mostly interested in asking students to 1) encounter a highly technical document and 2) leverage their existing knowledge to make use of that document. The idea here is that the distributed knowledge of the class permits us to render a previously obsolete document into a working plan. If it's not actually enacted, perhaps they could reproduce a more user-friendly version, something that a non-electrical engineer like me could use.

A draft of this pedagogical material can be viewed here. This is situated both as a usable document for teachers and as a component for a roundtable proposal for CCCC 2020. This course plan centers on accessibility and open access. In it, students develop accessibility remediation plans for information and facilities in their communities.

Systems of Boundary Objects and Boundary Object Function

My work is also inspired by my interest in the concept of boundary objects. Susan Leigh Star theorizes boundary objects as “objects which are plastic to adapt to local needs and the constraints of several parties employing them, yet robust enough to maintain a common identity across sites” (1989a, 393). In short, I understand boundary objects as things which can cross between domains, maintaining function and identity in both.Beyond conceptualizing boundary objects, Star suggests that further research, “[examine] the impact and combinations of boundary objects, and [begin] to develop a notion of systems of such objects” (1989b, 52). While boundary objects are singular, systems of boundary objects are plural and operate as ecologies. It is the function of boundary objects, as systems of boundary objects, that drives my interest in articulating a theory of design based on retrofitting obsolescence. If retrofitting obsolescence is the action, I think boundary object function is the feature that permits it to function.

Designing for Temporal Ecologies and Economies

Accessible design considers the ways in which all users find and meet technology. It asks that we design intentionally by incorporating points and modes of access for everyone, particularly those with differing levels and kinds of ability. Beyond accommodating disability, accessible design improves access for everyone. Perhaps design inspired by the prospect of obsolescence could be just as forward looking.Ecologies, as organized systems of function, and economies, as habituated systems of production, are spaces within which design operates. But ecologies and economies don't function in a vacuum, rather, they traverse space and time. Good design should, therefore, accomodate not only these system, but also changes they undergo. Perhaps an ethos of retrofit design is valuable not only for making old items valuable once again. Why could it not inform the ways new products are created? Could this be an alternative to programmed obsolescence and the design of "throw-away culture"?

I suggest that the best way to design with retrofitting obsolescence in mind is to design with a modular vision of the future. The future could turn out so many different ways! Of course, we can't predict them all, but what if we designed products (and ideas) so that they were intentionally malleable or receptive enough to adapt to several different possible futures?

A working plan forward

At this point in the project, I've made some exciting progress, but there is still much work ahead. In the USB Typewriter and my research experience with Hawisher's article on microfiche, I've discovered two examples that illustrate different aspects of retrofitting obsolescence. Gadbrys' work has been an excellent OA source working on very similar lines of thinking. The existing thoughts on theory and application are also highly motivating.

For here, the area I need to spend the most time with is reading and developing a more extensive literature review. At some point in my academic career, I developed the research habit of developing an extensive set of ideas before doing the reading--clearly is this not a good habit and it's one I'm working at breaking. Often this means changing those ideas once I work with new literature. This can result in new formations or new concepts all together. Giving up ideas we are enraptured by can be hard, but perhaps this is what retrofitting obsolescence feels like.

Comments

Post a Comment